Thursday, December 31, 2009

One year ago

Thursday, December 24, 2009

All I want for Christmas

My parents have asked me countless times in recent weeks if there's anything I'd like for Christmas, or something I need for them to bring from home when they fly out to meet me. It's been 8 months since I slept in my own bed, made myself a coffee with my espresso maker, or watched a Netflix movie in my queue, and while I miss these things from time to time, being on the road for so long has made me even less attached to "stuff" than before. Don't get me wrong, I still treasure my load of cooking gadgets -- I hope the juicer, the wok, the cuisinart, the pasta machine, the cheese-making kit, the brewing carboys are all being used in my absence -- and the boxes of books in storage. There will doubtless be a happy reunion with these things when I return to DC this summer. But as I have continued to pare down the supply of "things I need" as I haul the necessities around the country (which, collectively, are shockingly heavy even so), I find that there isn't much I lack. A new book from time to time, perhaps a map or some long underwear or a battery for my headlamp. I got Ollie a new set of front brake pads for Christmas: after a week off and a few plates of cookies under my belt, I want to be sure we at least are able to stop quickly when needed on the legendary switchbacked San Francisco hills.

As for me, now that I've been lucky enough not to die from a random bacterial infection in my thumb, I've not much to ask for. All I want for Christmas is a hug. And maybe a plot in my parents' yard to grow some heirloom veggies when I return, to supplement the tiny plot Shelly and I set up behind our place in the city. (Start digging up the back lawn, dad.) And, okay, maybe for my upcoming birthday I might not refuse a copy of Nourishing Traditions and a food dehydrator for when I get back home. (I'm totally hooked on drying fruit after the persimmon session at Jessica's last week and a dehydrator would round out my collection of odd culinary implements nicely.)

Happy holidays, faithful readers!

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Monday, December 21, 2009

Be the change you wish to see

The Noyo Food Forest was started a few years ago by a small group of dynamic women who had looked around themselves and been frustrated by a general lack of access to fresh local food while unused green spaces abounded. (It's not that there was nothing, but there wasn't much: a modest food co-op, one CSA, one small school garden.) Further, the decline of industry in this former mill town meant that many folks were disconnected from each other and the land. Morale was low in this isolated area. Taking Gandhi's mantra to heart, these gardening activists became the change they wished to see in the world: they began to build community gardens.

The first was the Learning Garden, which cultivates a plot of land behind the local public high school, utilizes buildings donated by the Mendocino County Office of Education, and is run by a small crew of devoted garden educators on the shoestring budget Susan cobbles together from sales and donations each year. Winding down its third growing season -- I learned from Sakina, the garden coordinator, as she showed me around -- the space has grown considerably from its humble beginnings, slowly expanding each year. It offers learning opportunities for adolescents and adults, supplies fresh produce to the school cafeteria and the farmers' market, and has been a point of pride for a number of high schoolers in the gardening class -- a well-attended elective -- who nurture the green oasis.

From the high school, Katrina, Susan, and I zipped over to the Head Start garden, where lunch and snacks are grown for the low-income-based preschool education program and an NFF staffmember runs weekly activities for youngsters and their parents. (Unfortunately, the timing of my visit didn't coincide with a lesson, but it sounds like a great program from what I can tell. Incidentally, improving child nutrition continues to be one of the strongest elements of Head Start programs across the country. It seems fitting that the tots and their parents learn how to grow and eat fresh, healthy veggies here.) Next it was over to the Come-Unity Garden, where we checked out 11 community plots and nibbled on apples as we admired the orchard under development. Then, after a brief walk around the town's only CSA (not an NFF project, but, really, it's all connected on some level and it was pretty impressive), we hotfooted it back to the Learning Garden to harvest fresh veggies and make a big salad for lunch. I needed my energy for the talk I was giving to the high school gardeners at 2pm.... They were a nice bunch, and asked lots of questions (mostly about the biking, though the adults sitting in prompted more questions about the farming and sustainable food pieces of my project).

Something that really impressed me during my time learning about the Noyo Food Forest was its amazing success with partnerships. This is partly because the need for pooled resources (money and land) brings NFF to the table with local groups -- schools, the Head Start program, the senior center (which I didn't have a chance to see), the Grey Whale Inn, Thanksgiving Coffee (site of the Come-Unity garden) -- but it is also because there are natural connections between gardening and so many aspects of community development. The gardens are sowing seeds of hope and awareness in Ft. Bragg: during one of our cooking sessions in the Inn's kitchen, Michael described the building of the garden at the Grey Whale as transformative, how neighbors had begun to stop by and admire the garden, complimenting the innkeeper -- who, until the garden, felt that he was considered an outsider here -- on its progress. He admitted to experiencing a quiet joy when immersing himself in the green space from time to time, sometimes incorporating the garden goodies into the Inn's offerings.

The Noyo Food Forest is working to empower folks to feed themselves, but the gardens are, in the process, fostering healthy communities as well. And not just here in Ft. Bragg. They have links to groups in places as nearby as Willits (30 hilly miles east) and as far away as Kenya (where a sister garden was started). It's the kind of program that could be replicated in many other places, adapted for different communities while maintaining its core philosophy. Gandhi would be proud.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Friday, December 18, 2009

Due to budget cuts, the outdoors has been closed

Indiana: Make the wind stop

Illinois: Home of Chicago's cycling mayor

Wisconsin: We brake for cows

(April's license plate is a close second, though, especially considering Growing Power's headquarters in Milwaukee.)

Iowa: #2 in wind

Minnesota: Our bike paths are great so long as you don't ride on them at night

Washington: The horizontal rain state

Oregon: Best bike touring state ever

California: Due to budget cuts, the outdoors has been closed

(Or should it be "the outdoors *have* been closed"? Shoot. And I used to teach English, too. Embarrassing.)

I really do hope the campsite situation improves soon. This closing of most all state campgrounds in California -- except, of course, for the ones with 50-cent showers and no way to make change to utilize said showers -- is putting a bit of a kink in my plans. Luckily I only have a couple more camping nights over the next week before visits with family and friends around Christmas.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Thursday, December 17, 2009

From the ground up

Prior to starting his own operation, Eddie had managed the nearby POTAWOT organic farm -- a local garden that provides fresh fruits and veggies to the Native American health clinic in Arcata. (Yes, a program directly linking healthcare and healthy food -- what a concept. Are you listening, Senators?) One morning when the ground was too frozen to harvest, and after we'd weeded the greenhouses, Eddie suggested that Ollie and I cycle over to check out the garden, health center, and hiking trails on the POTAWOT property. We did and I must say that it was pretty rad. Over the years, Eddie has continued to be an active member of the Arcata community and has fostered longstanding relationships with many in the small college town. So much so that when he decided to start his own farm, many of his CSA members were referred from the waiting list of another CSA farmer friend in town. (Farmers as collaborators rather than competitors -- not quite the conventional model, is it?)

When he started Deep Seeded Community Farm a year ago, Eddie explained, he could have found land further out of town for less money, an existing farm with developed soil and structures in place. But the most important element of the year-round CSA was for it to be accessible to its members -- who live and work in town -- so he's built it right in the thick of things, starting quite literally from the ground up. To Eddie, it is critical for families and friends to be able to connect with their food and each other. On CSA pickup days, Eddie chats easily with each of the 93 winter share members and their kiddos, exchanging recipe ideas, getting feedback on the quantity and variety of veggies, commenting on the unusually cold weather. They come by the urban farm each week to pick up their produce, sometimes also cutting fresh flowers in the spring or picking juicy strawberries in the summer. I overheard a few folks commenting on how they had finally gotten the hang of planning meals around the weekly boxes to use up all the produce, how they enjoyed the freshness and flavor of the new varieties available each week, and how glad they are that Eddie decided to offer a winter share (which, incidentally, was oversubscribed, but the farmer managed to produce enough to accommodate a few more people, as was the case with the popular regular season shares.) The farm and the food had become a part of their weekly routine.

I must say that the work itself seemed more manageable than some farms I've been to -- more sustainable in terms of human energy. At the end of the day, I was tired but not wiped out. Granted, it is the beginning of winter, so things slow down on farms everywhere. Eddie also confessed that he needed to maybe tone down the intensity a little in the farm's second year, that he'd put in ridiculous time and energy up until now. (I'm no slouch, but I was glad not to be banging on the frozen ground and sloshing around in rain as I had done at other farms prior to this one.) Still, he and the others I met while there seemed content and proud of their work. I enjoyed my time with the farmer and his part-time staff -- Jess, Scott, Rachel, and Will -- as we weeded, harvested, and washed produce. They were thoughtful and engaging conversationalists, passionate about food, energetic. At least two of them spoke of having their own farms in the not-too-distant future, I learned as we dug up carrots and snapped leaves of chard for the CSA. (Seriously, Will, I am going to look you up on my way through Mississippi.) During the slower cold months, in addition to evaluating the year's production and planning for the spring planting, Eddie is tinkering with the internship requirements for next season -- field work paired with an hour-long weekly seminar on a variety of topics. There is a lot of interest in local, sustainable food in Arcata, I would say (and not only because of the well-established and impressively stocked local co-op). The demand is here, the groundwork is being laid... Eddie is not only growing good food and a community of conscientious eaters. He's also helping to cultivate new farmers. Right on.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Let them eat kale!

(Serves 4-6 as a side dish)

Wash, remove the tough stalks from, and chop one large bunch of fresh, organic kale.

Put chopped kale into a large bowl and add a spoonful of salt. (Try between 1 tsp and 1 TBSP -- honestly, it depends on how much kale, what variety, and how tough it is.)

Toast a handful of nuts (almonds worked best, but sunflower seeds weren't bad, either) in a dry pan on the stove or on a cookie sheet in the oven for about 5 minutes. Cool, chop, and set aside.

Meanwhile, massage salt into the kale with your hands for about 5 minutes, until the kale is about 1/2 to 1/3 its original bulk and darker in color. (Don't be shy, get right in there with your knuckles. Like a good back rub. Ahhh, a back rub. Oh. Sorry.)

Add in:

• 1/2 small onion or 1 shallot, thinly sliced

• 1 apple, cored and thinly sliced

• 1 or 2 TBSP apple cider (or balsamic) vinegar

• a handful of dried cranberries (I think raisins or chopped apricots would work) or 2 sliced, ripe persimmons

• 1 TBSP olive oil

• freshly ground black pepper

• the chopped, toasted nuts

• 1/4 cup chevre or other soft, mild goat cheese (you can omit this to make it vegan, but it's darn tasty)

Stir everything together, serve, and enjoy!

I'm telling you, by the second or third day in the fridge, it's even better. (Yochi, back me up here.) I've made it three times already, including tonight with the mix of 3 kale varieties we harvested at Deep Seeded Community Farm earlier today. I know what I'm having for breakfast #1 tomorrow....

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Monday, December 7, 2009

In training

I see his point, but I think the parallel goes much further (as good metaphors often do). Long-distance cycling has pushed me farther than I thought I could go -- I mean, heck, my first ride was down the hall of Ben's apartment building and then I took the bus home, and now I'm nearly 3000 miles along! I've had many run ins with hunger, exhaustion, and less than ideal weather. Farming takes a heck of a lot of mental and physical strength and, to a degree, a denial of pain to push through the tough parts. I certainly am physically stronger than I was when I started. I know this for a fact because I didn't walk any of today's many long hills, including the 3.5-miler (who designs a 3.5-mile long uphill road??) and a few other substantial inclines along the 50-mile stretch. (Remember the days of the 0.8 mile high club? Ha!) Highway 101 does not kid around on the hills. So I'm stronger, maybe I will be less worn out baling hay or hauling bushels of carrots than before.

Farming is also about noticing things. The weather. How things grow. Pollinators. Pests. Sensing if something needs attention. Listening. To things like the thumping sound of a rear tire for the two or three seconds before it explodes as you're flying down the first big downhill stretch of the day. And being able to fix things when they break down. (Flat #8 of the trip is immortalized in the photo above.) I find myself noticing other things, too. Birds, wild onions, constellations. There's a quietness of mind needed, I think, to truly observe and listen, to be a good farmer. And the same is true of cycling.

A lot of people have asked me if I see myself on my own farm some day. Maybe. Frankly, I don't know if I'm tough enough. I've woken up with frost on my tent and frozen toes for the past three mornings and whimpered. I made my first phone call -- to my parents -- this morning from inside the sleeping bag. (It was so cold when I even poked my nose out that I snuggled back in for another half hour before I could work up the hutzpah to haul myself out into the frigid morning.) Tonight, with a forecast for freezing rain and 2 more days of serious biking until the next farm, I decided to dip into the slush fund and get myself a motel room (#6 of the trip). Would a real farmer do that?

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Thursday, December 3, 2009

How are we going to feed ourselves?

Lost Creek is one of the larger CSAs that I've been to, and yet it is run by a skeleton crew of David and two helpers (two fellow AmeriCorps alums, actually, so we had much in common and much to rant...I mean talk...about). The diversified farm has over 60 varieties of fruits and vegetables that it offers CSA members, small grocers, and local restaurants, and I learned from David that the region is considered by many to be one of the most productive in the country in terms of food. And yet, considering the consumption habits of the vast majority of Americans, there is a good deal of concern about whether this kind of farming (aka organic) on this kind of scale (still much smaller than pretty much any conventional farm) can actually feed our country. "It's not likely," David grumbled. The problem, aside from the skewed government crop subsidy system (don't get me started again), and a general pattern of undervaluing both food and farmers in this country (again, I'm restraining myself), David pointed out that the biggest problem is that there are simply not enough people *growing* the food in comparison to those (over)consuming it. We need to eat differently and eat less (especially less resource-draining meat). And where possible, we can do a better job of providing for ourselves. Yes, gardening.

I recall learning during my time at the Strawbery Banke Museum -- on my way through Portsmouth in July -- that during WWII something like 40% of all produce consumed in the country was grown in Victory Gardens. Yes, in people's front yards, school gardens, formerly empty lots. Forty percent! And now? Hardly anyone knows what brussels sprouts look like on the plant, or when strawberries are actually in season, nevermind how to save tomato seeds or when to start lettuce outdoors. "Food" comes prepackaged in gargantuan portion sizes from Costco and Walmart, ready to be "cooked" in the microwave. And then there's fast "food." Ugh. As a society, we've managed to sever just about every substantial connection to our food: how to grow it, cook it, enjoy it. But there's hope.

As a former classroom teacher, of course I believe that the paradigm shift that needs to happen for our food system to recover comes down to education. Understanding the difference between good food and crappy pseudo-food (what Michael Pollan terms "foodlike substances") is key. Some knowledge of what goes into producing food will go a long way toward understanding why good food costs more. For as hard as it is to grow and harvest organic carrots, they should be $10 a bag -- those suckers use up a lot of water and they are heavy to haul around the field in bushel crates! They should cost more, but not so much more in dollars than their chemically-dependent conventional sister carrots: there wouldn't be such an atrocious price difference between conventional/processed foods and organics if the *true* costs of food were taken into account -- in terms of labor requirements, environmental and personal health impact, and in the case of CAFO meat production excessive animal suffering. It would help if the government subsidies that I am trying not to harp on in this post were more conscientiously distributed. (Oops, I slipped.)

Still another part of the worldview shift will necessitate respecting the challenging nature of thoughtful, low-impact farming, not viewing food production as a mindless job that merely requires enough brute force, petroleum guzzling machinery, and a bunch of chemicals. (Some serious physical strength is needed, though. Whew!) I'll tell you, farmers, like teachers, work their tails off. To be truly great at either takes a special combination of talent and a lot of hard work. And while we all realize on some level that we need food (and critical thinking skills) to survive, we don't really value the people who feed us (or those who teach us). If we did, more people would *want* to be farmers (and teachers). And the work would pay better. These would actually be considered professions rather than just jobs that anyone can do. These days I feel like there is a perception that the work in either field is something left to those not smart or ambitious enough to do something better. It's no wonder most people want their kids to grow up and be doctors, lawyers, engineers, politicians. (There are some pretty idiotic politicians who have held office in recent years. If I have a kid one day, I hope my child grows up to be an organic farmer, or at least an avid gardener.)

How, then, can we begin to change the system? Seek out your local, organic farmers and buy directly from them as much as possible. Failing that, seek out small co-ops and markets who source from these farmers. While you support the important petitions of advocacy groups like Food Democracy Now to effect change at the policy level, don't forget to think about where you are personally spending your food dollars: you choose three times a day the food systems you support. (Unless you're biking across the country, in which case you choose about five times a day. What? I get hungry.) As Pollan would say, "We vote with our forks." Actually, while I'm at it, I'd advocate Pollan's most recent line: "Don't buy anything you see advertised on TV." Share the cooking and eating of good food with those you love. And for heaven's sake, get cracking on your victory garden.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

Where *not* to have a broken bike lock

Item 1: Waterproof, eh? Hardly.

Back in Pittsburgh, I bought a pair of "waterproof" cycling shoe covers at REI. It'd rained the better part of the first two weeks of my trip, so the investment seemed a wise (if pricey) one. But they were a bear to use. I swear I pulled a few muscles trying to shimmy them on every time, and then to zip them closed required the invocation of a contortionist with the patience of a monk and the strength of Samson (pre-haircut). I found that unless it was torrentially raining, I'd rather just have wet feet. This was all well and good until I began biking through SW Wisconsin at the end of September and the temperature started to drop just as the wind and rain -- that I'd been deprived of for whole days at a time during the stint in Madison -- picked up. I recall more than one occasion in Iowa and later in Washington State (aka the horizontal rain capital of the country) asking veritable strangers at campsites and folks I was staying with to help me get those blasted rain covers on. Oh, and also: once I finally had them on, they were only rain resistant, so once they were soaked through I had cold, wet feet that didn't let the moisture back out. By Eugene, I'd had enough and marched into REI. I returned them and bought neoprene socks. Like for scuba diving, yes. I've heard the material doesn't breathe, but it's waterproof and at this point, after months of biking with wet, frozen toes, I'm actually kind of looking forward to warm, sweaty feet. (Oooh, stinky. Probably doesn't make me such an appealing house guest, but I'm hoping my cooking and lively conversation outweigh the anticipated foot odor.)

Item 2: Indestructible? Ha!

Wouldn't you know it, less than a year after purchasing a brand new bike lock, the heaviest single item I've been dragging around the country, it crumbles in my hands in front of a Kinko's nowhere else but the bike stealing capital of the country: Eugene, OR. (It's true, ask any cyclist.) Luckily the nice folks at Kinko's let me store Ollie inside behind a display while I made some photocopies. The bike shop I'd bought the hefty lock from is across the country in DC, so I couldn't simply exchange it. You'd better believe I meant for the lock company to replace its faulty product, so I called them and told them as much. I don't want to get into the whole sordid tale, but I will say that I would have expected more from a "lifetime warranty." I bought a new one at REI, where words like "warranty" and "customer satisfaction" actually mean something. At least if this one breaks they will give me a new one on the spot.

Item 3: Functional? Only if today is opposite day.

I've about given up on the Verizon Navigator feature on the blackberry. Let's just call it the Windows Vista of the GPS world: it works occasionally and doesn't play well with other programs. Grrr. Good thing I picked up a book on cycling the Pacific Coast so I have a route pretty well mapped out. (Supplemented by the AAA maps you sent, dad -- thanks again!)

I'm feeling pretty good about things in general, in spite of the aforementioned product failures, and am really looking forward to exploring coastal Oregon and California in coming weeks. And if you're curious about how the neoprene socks are working out, rest assured that there will be an update (on the waterproof effectiveness as well as the stink factor -- all the better to keep curious marauding animals away from my tent at night, I say.)

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Friday, November 27, 2009

Make it the easier way

I love Portland. I'd heard quite a bit about the green city's devotion to all things sustainable before my arrival, and the rumors were confirmed during the 3 1/2 days I spent there. It was by far the most bikeable city I've encountered so far. It turns out, with the on-road bike routes and bike paths -- even designated lanes across most of the city's bridges! -- and racks scattered throughout all quadrants of the city, it is often faster and easier to cycle somewhere than to drive. Though currently only 1% of the city's transportation budget is devoted to cycling, it is a percentage the mayor's office is looking to boost in coming years, I learned from Amy, the advisor to the mayor on sustainability policy. During a chat and tour of the City Hall vegetable garden this past Wednesday, Amy told me about the city's green roofing requirements for newly constructed buildings and green roof retrofitting for many existing structures. I learned, too, of city government's investigation into the purchase of facilities to handle city-wide curbside compost pick-up. I didn't get the sense that there was much by way of residential recycling programs, which seems strange for so green a city in so many other ways. (Portland could take a few notes from Seattle and Olympia on that note; Seattle and Olympia could in turn take notes on the nicer weather here in Oregon.)

People seem to want to do the right thing here, but the trick is to make the "right" way the easier way. I have to admit that when I moved to Brooklyn a few years back, I was as much excited by the comprehensive city recycling program as I was about becoming a public school teacher, but the criteria for recycling was quite complicated. There were elaborate charts and color-coded bags. My landlord once chided me for not using the prescripted twine to tie my neatly stacked piles of old NY Times. We could have been fined. (This was mere months before the city suspended its recycling program for the meticulously rinsed and sorted plastics and glassware. I almost cried. Fortunately for New Yorkers, who generate a heck of a lot of trash, the program was restarted within a year.) Anyway, I get Amy's point and I agree with her: policies and processes need to be in place to make it easier for people to do things more sustainably. If it's too much extra work, most people, including the parents of certain food-minded cycling bloggers, won't do it.

The same goes for buying food: it needs to be relatively easy to support local, sustainable producers. While in town, I also had the pleasure of speaking with a few folks working at New Seasons, a local chain of grocery stores in Portland with a focus on local and organic products. It was something between a co-op and a Whole Foods, both in terms of products and pricing. I spoke first with Joey in the produce dept who told me of the cooperative nature between the 8-store-strong grocer and local farms. It's a delicate balance, I learned, to maintain a base of organic produce that is local and of a great enough variety to retain a steady customer base. I found myself seeking out primarily local produce, but the fresh ginger from Peru and the coriander from California also made it into my shopping cart. "People want to buy locally and seasonally these days," the produce manager pointed out, "But they also want things that don't grow in the region. We are still committed to local and organic as much as possible and we have strong ties to local farms." It's a challenge to maintain the quality and local connections at this scale, but New Seasons seems to be doing a pretty good job. I skipped the dairy section -- I didn't trust that I would be able to resist spending a pile of money on raw sheep's milk cheeses -- and next wandered over to the meat section, where I learned from Charlie that most of New Seasons' connections to local meat, poultry, and seafood farms are extensions from when the chain was a co-op, and all of the items they carry come from Oregon, Washington, and northern California. This is not somewhere I would have trouble shopping, though I'd have to live in Portland to do so -- the chain is determined not to expand to other parts of the country, though they do offer consultations on their business model to interested folks.

I spent my final afternoon and evening in Portland chatting and working alongside Abby of the awesome Abby's Table. The former personal chef had gone to a prestigious culinary school in New York and had worked for years concocting tasty, healthy meals for wealthy folks coping with serious medical conditions. Hence she does a lot of gluten- and dairy-free cooking as well as work with macrobiotics and raw food. (The raw crackers we nibbled on as we cooked and sipped kambucha were just scrumptious.) She'd moved to Portland fairly recently and had been on the lookout for an industrial kitchen out of which she could cater, host weekly communal dinners, and teach. "I realized that what I really wanted to do was empower people to find and prepare healthy food for themselves," Abby confided as we chopped leeks and pureed raw chocolate pudding. "It is possible to find fresh, healthy stuff to eat all year, but a lot of people don't know where to start. That's part of why I offer classes, to help show people the joy of cooking and eating. Sometimes they'll discover a new food at the market or they'll buy one of my sauces and get really excited to try a new recipe. They become more connected to their food."

Once they understand how easy it is to make delicious food, it opens up a whole new world. Abby belongs to a group of food specialists who teach courses for the Urban Growth Bounty series, an Oregon-based initiative that offers classes on everything from raising chickens and bees in your back yard to urban farming to cheesemaking and preserving tomatoes. The classes themselves range from about $15-40 -- a pretty accessible price -- though the series had ended for the year by the time Ollie and I rolled into town so I didn't have a chance to attend one. Now, if that isn't an example of the local policies making it easy to be active participants in sustainable city living, I don't know what is.

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

OMG, did he just misspell "agribusiness"??

During my time as a public school teacher, I was always expected to give some kind of project during school holidays. I tried my best to make these fun but thoughtful assignments. (Well, *I* thought they were fun; it's hard to please teenagers.) In honor of my former students, and inspired by a photo sent to me by my friend Mark earlier today, I've decided to hold a little contest....

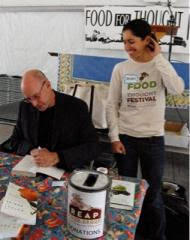

Your assignment, should you choose to accept it, is this: Come up with a caption for the photo above.

Historical note: It marks the first (non-photoshopped) photograph of me with one of my heroes, Michael Pollan. As you can tell, I was looking pretty menacing as the crowd control person at the book signing following Pollan's talk at the Food For Thought festival this past September.

So, put on your thinking caps and don't give in to the seratonin-induced food coma! I'll choose a winner on Dec 1 and send the victor a little care package from the west coast....

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Monday, November 23, 2009

Aw, shucks

I'd first heard of Taylor Shellfish during a chat with Dustin at Art of the Table one afternoon. I went home and looked the up the Washington-based operation, sent out an e mail, and was pleasantly surprised at the speedy and welcoming response from Bill inviting me to speak with him in person and check out a shellfish harvest at their farms near Bellingham or Olympia. (I was surprised as much by the kind nature of the invitation as I was by the fact that he responded at all. In my experience in Washington State, it takes a small miracle for folks to call or write back. I like to think this is because Washingtonians are too busy hiking or gardening or recycling to check their messages.) Anyway, the timing worked out such that I could join Bill and his colleague Marco on my way through Olympia.

I knew the quality of Taylor's shellfish was exceptional -- first, because Dustin had recommended them, and second, because I tried their wares myself. Repeatedly. Just to be sure. For the 3 evenings I was in Bellingham, Kendell, Kirsten, and I feasted on some variety of Taylor oyster, picked up at the Chuckanut shop: raw Virginicas, grilled Virginicas with an herbed mustard garlic sauce, broiled Pacifics on rye toast with more of that divine herbed garlic concoction. On the night I was slated to head out with Bill and Marco to check out their processing facility and a few harvest areas in Shelton (just west of Olympia) a week later, Marco invited me to make dinner with him and his wife. It was here that I learned how to shuck an oyster without accidentally slicing off any fingers. We sampled raw Olympias (quite salty), Virginicas (still my favorite), and Kumamotos (great with lemon) with a nice local wine before we got cracking on the main meal: sauteed scallops with fresh herbs, quinoa, and a warm beet green saute with roasted beets and carrots. We would need our strength, after all, to make it through the evening harvest with a low tide near 1am....

Now, I'd read something awhile back about oysters being used to clean up the Chesapeake Bay and thought, "Wait. Delicious food that purifies our water system? Seriously?? Why doesn't the EPA just dump a boatload of clams in the Potomac? I'll bring the garlic butter for stage two!" Well, I learned from Marco that in fact there are two different kinds of water pollution. There is the toxic variety -- sewage, say, or chemicals from a paper mill -- and the variety that is largely an excess of agricultural nutrients -- aka fertilizer, which causes a burst in algae activity when it leaks into lakes and bays. Oysters and clams and their brethren help address the second type, gobbling up the fertilizer-induced bumper crops of algae that, when mass quantities start to choke the waters as they decompose, would otherwise create "dead zones" -- large pockets of anaerobic underwater activity where fish and plant life cannot survive. Shellfish can help to remediate the effects of industrial ag! At least that was my understanding of the interplay between agricultural runoff, aquatic life, and the mollusk solution. (Now don't go dumping NPK all over the place....)

The beautiful thing about sustainable shellfish farms is that the clams, oysters, geoducks, and mussels clean the water and support (rather than compete with) a healthy aquasystem as they grow. Taylor is meticulous about managing the populations so that the ecosystem remains in balance. It's a very non-invasive operation, so much so that even the PVC cylinders that are used to protect tiny oysters from predators are later coopted as habitat by other underwater creatures. And consider that no chemicals and very little fossil fuel are needed to raise them. They're pretty low maintenance, which may be why folks are starting to get into small-scale shellfish farming all along the coast. All the while, the shellfish farms are producing a tasty, nutritious, renewable food source. Those little guys are packed with vitamins and protein. If you're into that kind of thing. Me, I'm into their amazing tastiness.

You may be wondering what that odd looking thing is that Marco is holding in the picture. Don't worry, this is a G-rated blog. (Or at least PG-rated.) He's holding a geoduck, the first one I had seen up close, though not the specific one that squirted me in the face when Marco hauled it out of the water. I didn't actually see geoducks getting harvested -- we checked out oyster and manila clam operations when I was in town -- but they're really odd looking and fascinating creatures and warranted a photograph. They're the largest burrowing mollusks in the world and some live over 100 years. And they're tasty. I realized when Marco informed me that it's what's known as "giant clam" at sushi restaurants, that I might've eaten this guy's cousin two weeks ago in Seattle. Maybe the eye squirt was the bivalve equivalent of vengeance.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Saturday, November 21, 2009

The namesake

We got to see a good bit of the north and west sides of town when, mapless, we got somewhat lost on the way from Evergreen College (where I'd joined a potluck and sat in on a film and lecture on pesticides) to Shae's house (where we would be staying); we saw much of the east and south sides heading out of town. Another hilly city, what a surprise. Cute, though, and home to two food co-ops. (We visited both, of course.)

Thursday evening before the trip out to some of the Taylor Shellfish sites to see clam and oyster harvesting in action, Marco, Lalita, and I feasted on fresh seafood at their home -- including tiny, salty, raw Olympia oysters (which, incidentally, had been endangered up until just a few years ago, before groups like Taylor had dedicated efforts to cultivate these tasty native bivalves) and carrots and beets pulled right from the garden. I think the wine and quinoa were sourced a bit further afield, but still: delicious.

Friday, after a trip to the Olympia Coffee Roasting Company for a cup of outstanding fair trade java, we stopped by the town's famous Artesian Well to fill up our water bottles with what was rumored to be the best water anywhere. (It was certainly a heck of a lot better than the water in Iowa. Yeah, I'm talking to you, Des Moines.) The barrista at the coffee house warned me that folks who drink the well water were bound to return to Olympia... or never leave it. (Oooh, foreboding. I triple checked Ollie's tire pressure this morning before we left. Not that it's a dreadful town, but we do have quite a bit of the country yet to explore.)

Friday afternoon, I met with Kim, one of the founders of GRuB -- a community garden and youth empowerment project in town. She gave me a tour of the gardens and told me about some of the cool programs GRuB is involved with: the construction of 100 free kitchen gardens each year for low-income families in the area, the training and employment of at-risk teenagers to grow food for sale at the farmers' market, donations to the local food bank. Sounds like my kind of nonprofit, and Kim helpfully suggested a few other programs to check out as I make my way south through Oregon and California.

Friday evening, I was invited by Ian, of Olympia's own "The Bike Stand" bike shop, to join a few friends for some of the finest local (organic) microbrews around and a plate of fish tacos. Mmm, local cod and cilantro. They say its the great water that makes for such tasty pints at Fish Tales, and I am not altogether unconvinced. Were I not slated for an intense day of cycling the following morning, I more than likely would have tried a few more of them. (I wonder if the town water's mystical properties apply to the beer as well.)

As we make our way toward Portland, I've noticed that Ollie seems a bit sluggish. Most people might think it's the headwinds or the near-constant rain or the unanticipated hills slowing us down, but my hunch is that it's the water trying to draw us back. Onward, Olympia!

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Thursday, November 19, 2009

The Great Pumpkin

So I am, admittedly, a little obsessed with pumpkin. Pumpkin beer, pumpkin and bacon pasta, pumpkin bread.... There was the time in grad school when my cousin Sonia and I decided to make curried pumpkin peanut soup one night. (I thought my boyfriend Adam was going to pass out from hunger, since we didn't finish making it until near midnight. It was damn good, though.) There's the pumpkin ale I made with my boyfriend Nick and my cousin Caroline a few years later when Nick was just starting to tinker with homebrewing. (Dad and I still reminisce about sipping on it that Thanksgiving.) I even took part in a pumpkin-themed Iron Chef competition with some of my brother's friends a few years ago. (With broiled, bacon-wrapped pumpkin spears, and spiced pumpkin seed-marinated grilled turkey legs, we totally should have won. I think it was rigged.)

These gorgeous gourds may be one of my favorite things about autumn. I have, however, in my ongoing quest for pumpkin-related recipes noticed quite a trend toward canned pumpkin. Fresh pumpkin (halved, roasted at 400 degrees for an hour or so until soft enough to scoop out and mash) must make an infinitely superior pie, muffin, etc., much as my brother's sweet potato pie with roasted, mashed sweet potatoes puts the canned competitors to shame. (Yes, aside from large hunks of grilled meat, my kid brother makes a mean sweet potato pie. Though I think his signature dish these days is the french onion soup. Ah. Right. Back on point: pumpkin.) The stuff from scratch must be better, right? I don't know that fresh pumpkin is any more sustainable than canned -- and in fact it makes sense to can some of it for later use -- but when the fresh stuff is available, shouldn't you use it? I'm researching food and clearly this research (tangent) needed more data.

Realizing that it may be some time before I have the luxury of a well-stocked kitchen at my disposal, I decided this afternoon to do a little experiment. I stopped by the market and picked up an organic pie pumpkin and a can of organic pie pumpkin (which listed only one ingredient: organic pumpkin) and got cooking. I adapted a recipe from the Nov 2002 issue of Bon Appétit (Spiced Pumpkin Muffins), making two batches: one with real pumpkin, one with canned. I don't like using sugar when I can avoid it, so there were a number of changes to the original. I did my best to document what I actually did and wrote down the approximate measurements. (Those of you who have cooked with me know I am more of a "handful of this" in my estimates, so it took some work). In honor of Charlie Brown, I give you...

The Great Pumpkin Muffin (makes 12 large or 15 standard size)

Preheat oven to 375°F.

Butter and flour muffin pan.

Whisk in large bowl to blend:

• 1/2 cup all purpose flour

• 1 cup whole wheat flour

• 2 1/2 tsp baking powder

• 1 tsp ground cinnamon

• 1/4 tsp ground cloves

• 1/2 tsp salt

• handful of chopped pecans (unless you're Felicity, in which case you'll try to substitute trail mix -- busted!)

In a separate, medium-sized bowl, stir together:

• 1/2 ripe organic banana OR 1/3 cup apple sauce

• 3 TBSP honey

• 1 1/2 cups roasted pumpkin OR 1 can organic pumpkin

• 1/2 cup skim milk

• 1/2 cup whipping cream

• 2 large eggs

• 6 TBSP (3/4 stick) butter, melted

• 2 TBSP grated, peeled, fresh ginger

Add to dry ingredients and stir just until incorporated (do not overmix).

Spoon 1/4 cup batter into each cup. Bake until muffins are golden and toothpick inserted into center comes out clean (25-35 minutes).

Turn muffins out onto rack and cool. Store muffins airtight at room temperature. (As if you can resist eating them long enough for storage -- ha!)

If you want to fancy them up, make a frosting by blending the following:

• 1/2 stick (4 TBSP) room temperature butter

• 8 ounces of cream cheese

• 1/2 tsp vanilla

• 1 tsp lemon juice or 1/2 tsp powdered ginger

• 1 TBSP honey

When he came back from work, I accosted Kevin to give me feedback on frostingless candidates. After a blind taste test, here's the verdict:

Flavor: fresh pumpkin wins with a stronger, more pumpkinny presence -- Aha!

Texture: canned pumpkin wins with a moister springiness -- Doh!

In retrospect, I think I would puree the roasted pumpkin, which might make the muffins a little airier. In the meantime, I'll see what folks think when I bring some of each to the potluck tomorrow in Olympia....

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Sunday, November 15, 2009

The permaculture puzzle

After breakfast, I spent Saturday morning with a group harvesting medlars. You're probably wondering what the heck a medlar is. I didn't know myself until we got out to the orchard and started gathering windfalls (fruit knocked down by the wind) of these rose family relatives. The rock hard, alien looking fruits soften into something like a paste over the course of a few weeks after harvesting, I was told, and are excellent in preserves. The trees, I believe this particular variety was of English origin, grow amazingly well amid Orcas Island's mediterranean-like climate and are prolific producers of tasty edibles. Why, then, have I -- self-proclaimed lover of all fruits from around the world and a former graduate student of English Literature, which surely must have some mention of the cultivar -- never heard of a medlar? It is one of hundreds, maybe thousands, of varieties of fruit and nut trees that have been uncultivated by the modern food production system and have thus fallen off the food radar. These are the sorts of plants that the Bullock family is seeking to explore for their potential to round out a thriving ecosystem, where humans live in harmony with the land and the land, in turn, provides a year-round cornucopia of edibles. The loss of connection between people and the plants that feed us is part of what permaculture seeks to remedy.

I had no expectation that I would be able to tease out a one-sentence working definition of the term during the brief period I spent working with the Bullocks and interns at the homestead. Heck, I hardly had hopes that I could wrap my head around the general concept enough to attempt a blog post on the topic. But I asked. "Permaculture is something that takes many years to really understand," Doug proposed (in a very kung fu master kind of way). I asked Yuriko what it meant as we separated and potted strawberry runners. I asked Lily as she made bread and Emmett as he showed me around the nursery and the far fields....

Before coming here, my vague understanding was that permaculture was a way of farming that was meant to establish food growth cycles that would require progressively less human effort. I was not altogether off the mark, but the ideas involved go far beyond low maintenance food production. From what I can piece together now, it seems that permaculture is more a way of thinking than a set of specific agricultural techniques. It is a lens through which we can view our relationship to the environment and set things up in a way that is mutually beneficial and requires the least amount of energy. (Not just fossil fuel energy but human energy as well, which is something oft neglected by overworked organic farmers.) Like most worthwhile pursuits, it takes careful observation and thoughtfulness: an awareness of how various elements of the particular ecosystem work; understanding what each part contributes and what it needs to flourish; knowing which areas get more light or less water. People play an integral part, not as reckless consumers nor rabid preservationists but rather as stewards coaxing an increasingly healthy balance throughout the system, all the while sustaining ourselves.

The philosophy seems to invite people to conceptually divide up whatever space they are managing and take into consideration which things need more attention, placing these where they will be most accessible, relegating the less "needy" things to further removed areas. (What a metaphor for life, no?) On a farm, herbs might be easily accessible from the kitchen door, the orchard farther afield, the low-maintenance potato patch further still, the berry bushes that ripen during summer months planted along the path to the swimming hole where people can enjoy a handful of raspberries on the way or pick a few pocketfuls of blueberries for a pie on the walk back. In an apartment building, it may mean finding herbs that do well in planters that get only indirect light or starting a windowsill or balcony garden with plants appropriate for the particular climate zone. More than anything, permaculture encourages a return to common sense (which, sadly, so many of us seem to have lost -- me included, I realized, when someone had to show me how to use flint to start a fire) and utilizing the resources we have at our disposal.

The core of permaculture seems to entail being mindful of the different factors affecting your surroundings and understanding how you can nurture the best each piece of the puzzle has to offer (not necessarily in terms of amount but rather quality, though there is something to be said for quantity). It is something you can do in rural Iowa, on an island in the South Pacific, in a New York apartment, and that's part of what makes it so cool.

So there you have it: permaculture demystified. After two full days of working and questioning and observing and pondering, I wonder: Doug, how'd I do?

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Saturday, November 14, 2009

Getting down to business

On Wednesday afternoon, after a quick trip to the local food co-op (one of two, actually), I hiked over to meet with Laura who had recently taken over the Food & Farm Manager position at Sustainable Connections. As it was an unusually beautiful day, we decided to take a walk while Laura brought me up to speed on some of the innovative work her organization is doing to foster collaborative relationships among local vendors and promote thoughtful business practices. From waste reduction to green construction, Sustainable Connections -- I'll call them "SC" for short (probably not approved by their marketing dept, but it's a bit long to keep typing on the blackberry) -- seems to have helped quite a number of local groups become even more conscientious community players. I learned, for example, of the partnership between Mallard's ice cream shop and a number of area farms when Laura and I chatted with SC member Ben while he offered us samples of his tasty wares: apple pie, grape, and pumpkin were among the featured flavors with local, seasonal ingredients. (My favorite learning experiences always involve food -- what a surprise.) When farms have a bumper crop of berries or basil, they ring up Ben and drop off a few crates. Then the flavor experimentation begins.

What I was most intrigued by during my chat with Laura was SC's "Food to Bank On" farm mentorship program, whereby farmers just starting up in the area are given the opportunity to work with established farmers on everything from creating a business plan to troubleshooting during the growing season. Not only that, but the first year -- I think it was only for the first year -- new farms are guaranteed a market, selling a portion of their products to the local food pantry. I was curious to speak with some of the participants in the program.

On Thursday, Kirsten, Kendall, Marco, Lupe, and I hopped in the truck to visit a few nearby farms, including one listed on the SC business roster: Hopewell Farm. After admiring the kale and chard in the garden, Kirsten and I wandered to the farm stand where I was instantly taken with the gorgeous romanesco (a variety of cauliflower, I believe, with wild, beautiful spirals, and delicious when roasted with fennel seeds and kalamata olives, I would learn that evening). We struck up a conversation with Tiffany -- pictured here with the striking swirled brassica -- and Dorene, the farmer's wife. I learned that along with the mentoring and food bank elements, members of the SC also enjoyed benefits like discounts at fellow members' operations and regular opportunities for business development. While Hopewell was no longer an active mentor farm, and past experiences with that particular initiative were mixed, Dorene agreed that the benefits of SC membership were many and varied, and my impression was that she was among many happy local participants.

I'm hoping to follow up with a few more folks to hear their thoughts on SC's impact in Whatcom County, but so far this seems like a pretty amazing business community.

Sent from my Verizon Wireless BlackBerry

Sunday, November 8, 2009

Under the radar

After some navigational mishaps -- a few wrong turns and a route that took me up what must be the most gigantic hill in the city (I don't know why I have any faith at all in the "bike" setting on the GPS, considering its track record, but I keep hoping) -- Ollie and I made it there. Not only that, but I had the good fortune to snag one of two seats at the kitchen window and treated myself to a glass of wine and a small plate (okay, two: I couldn't decide between the crepe and the flan, and even now I doubt I could choose between them) while I watched the two chefs at work. They moved about the small space effortlessly, gracefully, almost silently, as if they were two hands rather than two people, and as I nibbled I couldn't quite bring myself to interrupt the flow with a jarring, "So tell me, where did you find these amazing huckleberries?" or "Now, how exactly do you design the weekly menus?" I left with a happy tummy but a lot of unasked questions. Well, that wouldn't do.

The next day, I called to see if Dustin, the head chef, might be amenable to chatting with me a bit about his food philosophy and his connections with local producers. I got the voicemail and blathered on for entirely too long, and yet a day or two later he called back and nonchalantly invited me to drop by during Saturday's dinner prep. So I did.

I spent the better part of the afternoon entranced as Art of the Table's dynamic trio prepared for the evening meal. I'm not sure they knew quite what to make of me, perched on a stool by the sink, half the time simply transfixed by the smooth precision of the two men moving about the kitchen while Laurie got the dining space in order. When I wasn't rendered speechless watching Phil pat each individual squash ravioli into shape or Dustin meticulously remove tiny bones from a salmon fillet or check the marinating veal cheeks for the evening's supper club, I managed to learn a bit about the tenets behind the food. Dustin's training in the French culinary arts may explain his expertise combining flavors and textures -- and the food is truly exceptional -- but what I admire most about the quietly intense culinary artist is his fanatical adherence to using only local, sustainable ingredients. The evening meals he and Phil painstakingly prepare are all made from scratch and sourced within the state. (Except for beef, he admitted, which sometimes comes from as far away as... Oregon. Oregon! Whose border is a day's bike ride away!) He spends hours each week scouring the farmers' markets, even on his days off, and has built strong relationships with local producers of everything from salmon to bacon to chocolate. Dustin's the real deal, a locavore in the strictest sense (although my guess is he'd probably never use such a trendy term to describe himself).

His outlook on the culture surrounding food is imbued with European sensibilities, and it's something, he proposed, that has been largely lost in our modern American lives. Food appreciation is experiencing a revival a few evenings a week here, though. I learned from Laurie, who manages the restaurant's logistical details, that folks making reservations for one of the supper club dinners rarely know ahead of time what will be on the menu. They simply know the theme -- this week it was "Italy" -- and trust that the chef will delight them with local, seasonal inventions. And he does. (While I didn't stay for the dinner -- unfortunately it was not quite within the current ABF budget -- I did take a look at the final menu and will likely be dreaming about it for some time.)

Like Anne Catherine, the local food aficionado whom I'd spoken with earlier in the week, Dustin hadn't moved to Seattle with a plan to open a restaurant. After years of cooking on ships and working as a private chef, he'd been looking to do some catering. He came across the restaurant space and got to thinking and, well, the rest, as they say, is history. "I could do this for the next 20 years," Dustin told me, matter-of-factly. "Here, I focus on the food," he asserted, unabashed. "I don't advertise. People find me through word of mouth. They know what I'm about and they come here because of it. They appreciate it. I'd like to keep it that way. I'd rather be under the radar." A renegade foodie. I like it.

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Always in season

Ollie and I returned on Tuesday morning as Anne was getting things set up to accept deliveries from a number of local farms. Unpretentious and welcoming, she offered me a seat and a glass of local cider and in between periodically signing for deliveries shared a bit about how she came to run this small, all-local (with the exception of perhaps the salt and breakfast tea) eatery. Her background in cooking comes from a lifelong passion for food, years of working on ships as a chef, later attending the highly-esteemed Le Cordon Bleu cooking institute. She hadn't intended to open a restaurant when she came to Seattle, she admitted, but was looking for a space with a commercial kitchen to teach cooking classes and host regular, seasonal group meals. It just kind of happened.

As we continued talking, I admitted to my fascination with the direct link between the kitchen and local producers. I had even sought out a few of the farms listed on the menu at the Ballard farmers' market after leaving the restaurant, and a few of the vendors mentioned that some of their customers had discovered the products via Anne's menus. (She seemed genuinely excited to hear this.) When I asked how she selected producers, I learned that the locavore had established relationships with growers at the farmers' markets over many months, first doing her personal shopping there and then later sourcing ingredients for the professional kitchen. Because of her fierce devotion to local ingredients -- "Why would I use blood oranges from California when apples and pears are in season right here?" -- she's developing a reputation among local producers who are now seeking her out to feature their local veggies, wines, and more. While she tries out a new supplier now and then, Anne's loyalty to the farms who supply her all year long are the backbone of her operation. As these partnerships have flourished, she strives to work with what the farms have available. Because of her steady support farmers often ask if there's anything she would like them to grow. "No," she insists, "Grow what you want and I will cook it." Much like CSA members are given a box of "whatever the farm has" each week, the Caprice Kitchen may well be the truest iteration of an RSA I have encountered.

Chef Anne Catherine may be one of the few people I have met in my life who loves food as much as I do -- she relishes opportunities to experiment with fresh ingredients, cook up a storm, and share it with people. Even on her rare days off she can be found foraging for wild mushrooms or visiting farms. (She had just gone searching for chantrelles the day before I stopped in. Oh, if only I had known I would have tried to talk her into taking me along: I'm dying to go mushrooming!) The business, even now as the restaurant is about to celebrate its one-year anniversary on Thanksgiving, is more about reconnecting people with delicious, in-season food and supporting local growers than turning a profit. (The operation does make enough to cover its costs, so I'm hopeful it will be around for a long time.) I would be lying if I didn't confess that a small part of me kind of wants to linger in Seattle a bit longer to see what will be on the menu next week....